The Importance of Scientific Research in Professionalizing Agile

Written on

In recent discussions within the Agile community, I have urged a shift towards valuing scientific research over anecdotal evidence. My concern stems from a growing dependence on authority, personal anecdotes, hearsay, and idealistic thinking, which I believe contributes to the decline of Agile practices. Claims made without solid evidence can harm our profession, as it raises doubts about the validity of the methods we promote to teams and clients. How can we be sure that what we advocate isn’t just empty promises? The current standards for truth in our field are alarmingly low.

I am not alone in this viewpoint; figures like Nico Thümler, Karen Eilers, Luxshan Ratnaravi, Takeo Imai, and Joseph Pelrine echo this call for a more research-oriented approach. Since my initial appeal, I have engaged in projects aimed at integrating more scientific inquiry into Agile methodologies, including a series of blog posts that summarize research on various Agile-related topics. However, I have encountered resistance from parts of the community, with many individuals approaching me to express concerns about how this shift may impact their work.

This article seeks to address common criticisms and questions regarding the integration of scientific research into our domain, while also clarifying what my call to action does not imply.

Why is Scientific Research Significant to Me?

The Agile discipline, while relatively new, is full of passion and ideals. A brief glance at platforms like LinkedIn or Serious Scrum reveals numerous strong convictions about what constitutes effective practice. Many of us are motivated by noble aims such as "delivering value," "creating humane workplaces," and "enabling empirical practices." We also hold various beliefs about the means to achieve these goals, often favoring specific frameworks like Scrum or Kanban while dismissing others like SAFe.

Disagreements abound regarding team composition (e.g., diversity versus homogeneity), necessary roles, preferred practices, and essential cultural traits within organizations. Each individual has beliefs about the most effective ways for teams and organizations to function. However, lively debates on social media illustrate the divergence in opinions. For instance, some assert that product managers and product owners are identical roles, while others vehemently disagree. The same is true for contentious issues like estimation practices. These debates are empirical in nature and can be resolved with adequate data, yet such efforts are seldom made amid the flood of personal opinions.

Scientific research holds personal importance for me as it provides a systematic method for discerning truth in our world. When executed properly, it minimizes biases and enhances our understanding of how things function. As a professional, I feel ethically compelled to adopt methods that are effective and discard those that are not substantiated by evidence. Furthermore, I believe it is my ethical duty to support claims with evidence that correlates with the strength of those claims. For example, if I assert that "All Scrum Masters need technical skills," I must provide evidence from a diverse sample of Scrum Masters and their teams' effectiveness.

If such evidence is lacking, I should temper my claim to reflect the evidence available: "Based on my experience with X teams, Scrum Masters with technical skills appear to foster more effective teams." This is where scientific research comes into play. It serves as the best means to validate our assertions regarding practices and guidelines, as well as to challenge unsupported claims.

Value of Individual Experiences

Numerous Scrum Masters and Agile Coaches share their personal narratives through blogs and social media. Does my advocacy for scientific evidence imply that these experiences are irrelevant?

Not in the least. Individual experiences are valuable, as the scientific method is grounded in the premise that knowledge stems from our sensory experiences. Personal insights from working with teams can provide indications of effective practices. For instance, one might observe that smaller teams tend to perform better than larger ones, or that pair programming enhances code quality.

However, the challenge with personal experiences is their susceptibility to biases. Our cognitive processes often lead us to remember instances that affirm our beliefs while overlooking those that do not (confirmation bias). If I am convinced that team stability is crucial, I am more likely to recall instances supporting that belief. Additionally, selection bias can skew our experiences to fit our views. For example, my background in small organizations has shaped my belief that Agile is more effective in such environments, despite objective data suggesting otherwise. An extreme version of this is the "N=1 bias," where a single experience is generalized to all situations, which is common in discussions of "best practices." This can result in outright rejection of estimation practices based solely on personal experiences.

In essence, individual experiences can highlight potential patterns, but we cannot confidently generalize these patterns to other contexts without robust evidence.

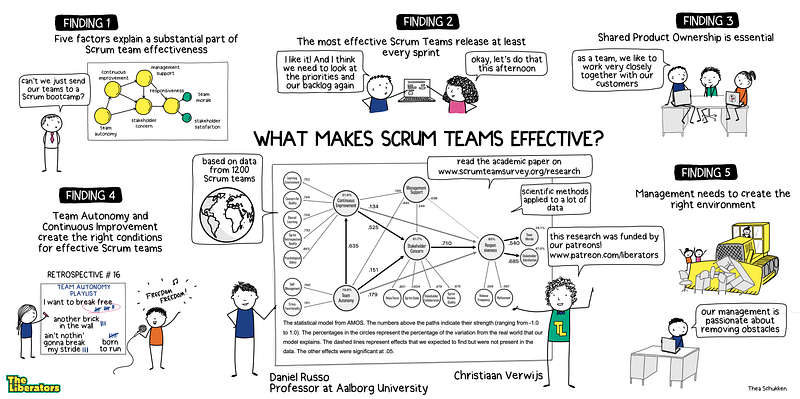

In summary, while personal observations can reveal potential trends (e.g., "SAFe negatively impacted my organization" or "Pair programming enhanced our code quality"), these insights cannot be confidently transformed into universal claims without substantial evidence. Generalizations are only valid when they derive from a representative sample of experiences that confirm the observed pattern. This is the goal of many scientific disciplines: to identify patterns from individual experiences (qualitative research) and validate them across a broader population (quantitative research). For example, we can assert with reasonable confidence that teams operate more effectively when psychological safety is present (Edmondson, 1999) and that frequent releases correlate with stakeholder satisfaction (Verwijs & Russo, 2023).

Should We Only Consider Experimental Evidence?

A common counter-argument is that while scientific evidence is recognized as valuable, the criteria set for acceptable evidence can be so stringent that it excludes much relevant data. This leads to the dismissal of various claims due to the perception that experimental evidence is the only valid form.

For instance, some insist that only evidence from double-blind, controlled experiments is acceptable. Such studies involve manipulating a variable while maintaining other factors constant and measuring outcomes. If changes occur, the effects can be attributed with high confidence to the manipulated variable. Ideally, neither the participants nor the researchers know what is being tested (double-blind). While these studies do provide strong confidence, it is unreasonable to demand this level of rigor across all scientific fields.

Controlled experiments are feasible in certain scientific domains, such as physics or medicine, where variables can be managed. However, in many other areas, particularly in social sciences and organizational research, controlling every variable is impractical or unethical. Historical researchers cannot alter past events to observe outcomes. Similarly, organizational researchers cannot maintain uniform conditions while implementing new methodologies.

Experimental designs, while powerful, do not suit every research question or context. Many systems are too intricate, with countless variables influencing outcomes—such as culture, personality, and situational events. There are also ethical concerns, as we cannot subject teams to harmful stress to assess their responses. Instead, researchers utilize a variety of methods, including observational studies, case studies, theoretical models, and meta-analyses, to gain a comprehensive understanding of phenomena. Each method has its strengths and limitations, making the choice of approach contingent on the research question and available resources.

Consequently, we should evaluate evidence from diverse methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, surveys, correlational studies, etc.) to assess the validity of claims. Academic communities often publish meta-analyses and literature reviews that synthesize scientific evidence on topics like psychological safety and effective leadership. Resources like Google Scholar (using the “Only reviews” filter) can help locate such studies.

In summary, insisting that only experimental, double-blind studies qualify as scientific evidence is unreasonable. Such a stance would dismiss most scientific findings and undermine the scientific method across numerous fields. Instead, we should familiarize ourselves with the scientific consensus on relevant topics and use this knowledge to discern which claims are evidence-based and which are mere assertions.

What This Means for Your Practice

My appeal does not expect everyone to conduct scientific research personally. While I encourage more community-driven research, proper scientific inquiry requires specialized skills.

Looking at established professions can provide insight. Psychologists, for example, have organizations like the APA that train, license, and support research initiatives. Engineers have the IEEE, architects the AIA, and project management professionals the PMI. These institutions serve to protect their respective fields. In Agile, the Agile Alliance is the closest entity we have, while others, such as Scrum.org and Scrum Alliance, operate on a for-profit basis. Although they may engage in research, their primary focus is on commercial offerings rather than the advancement of the profession.

Since we lack robust non-profit organizations akin to the APA or IEEE, it falls upon professionals to safeguard our field. Here are some actions you can take:

- Avoid making unsubstantiated claims to clients or on social media. Statements like "SAFe is detrimental to Agile" should be framed as personal opinions rather than definitive assertions.

- To evaluate claims' validity, consult the scientific consensus. Google Scholar can be an excellent starting point for finding recent review articles. While academic articles can be dense, their summaries, introductions, and conclusions often provide useful insights.

- Contribute to scientific research by collaborating with academics like Daniel Russo, Nils Brede Moe, or Maria Paasivaara, who often seek study participants.

- Encourage others on social media to substantiate their bold claims with evidence. If their arguments hinge solely on personal experiences or anecdotal evidence, we should treat such claims with skepticism until they are backed by data. Promoting this practice within our community can enhance the professionalism of our field.

Closing Thoughts

This article responds to some feedback I received regarding my call for the Agile community to place greater emphasis on scientific research rather than personal narratives. The necessity for more scientific inquiry in our profession remains pressing, as it can elevate our standards and enhance the value we provide to teams and organizations—moving us away from unsubstantiated claims. Although this journey may be challenging, particularly in the absence of independent non-profit institutions, it is vital that we begin to progress in this direction collectively. I have outlined several actions you can take within your practice to support this initiative.