Exploring the Science of Psychedelics: Insights and Applications

Written on

This article represents Part 3 of a comprehensive five-part series on psychedelics. This series is designed for those looking to expand their knowledge on various aspects of psychedelics.

Part 3 focuses on the scientific underpinnings of psychedelics. For prior installments, please refer to Part 1: Understanding Psychedelics and Their Historical Context; Part 2: The Psychedelic Experience; Part 4: Safety Considerations in Psychedelic Use; and Part 5: The Business Landscape of Psychedelics.

I invite dialogue from anyone involved in this field, be it startups, investors, activists, researchers, or healers. Feel free to reach out through my personal website, Twitter, Instagram, or LinkedIn.

PART 3: THE SCIENCE OF PSYCHEDELICS

This section provides an introductory look at the science behind psychedelics.

Pharmacology

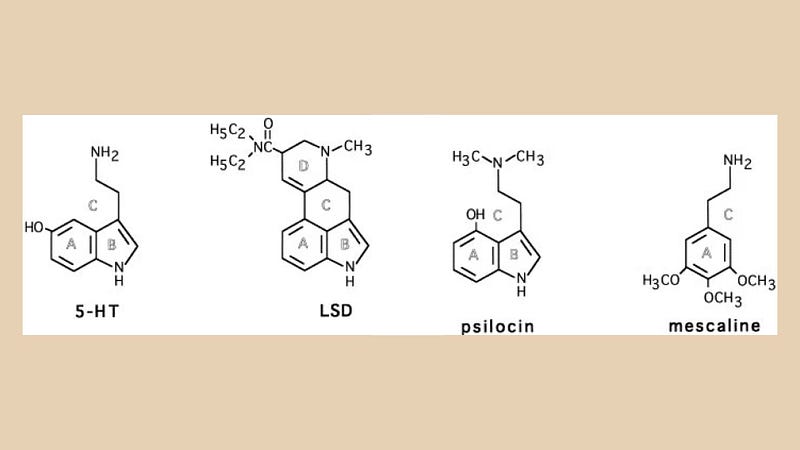

Psychedelics are substances that influence brain function. To grasp the chemistry of these compounds, we begin with serotonin. Serotonin (5-HT) is a neurotransmitter pivotal for transmitting signals within the brain, affecting various functions such as mood, sexual desire, sleep, appetite, memory, and learning.

While attributing conditions like depression solely to low serotonin levels is an oversimplification, there is a connection; increased serotonin can alleviate symptoms. Consequently, many antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that elevate serotonin levels by preventing its reabsorption.

What role do psychedelics play? A variety of them, such as LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT, act as serotonin receptor agonists. This means they bind primarily to the 5-HT2A receptor sites in the brain, mimicking the effects of serotonin. However, the precise mechanisms through which psychedelics alter perception and cognition via the 5-HT2A receptor remain unclear. Additionally, these molecules interact with other receptors to varying degrees, which contributes to the distinct effects of different psychedelic substances.

The accompanying image is derived from a 1999 Yale study titled "Serotonin and Hallucinogens," which highlights the structural similarities between serotonin, LSD, and psilocin (the active form of psilocybin after digestion).

Applications

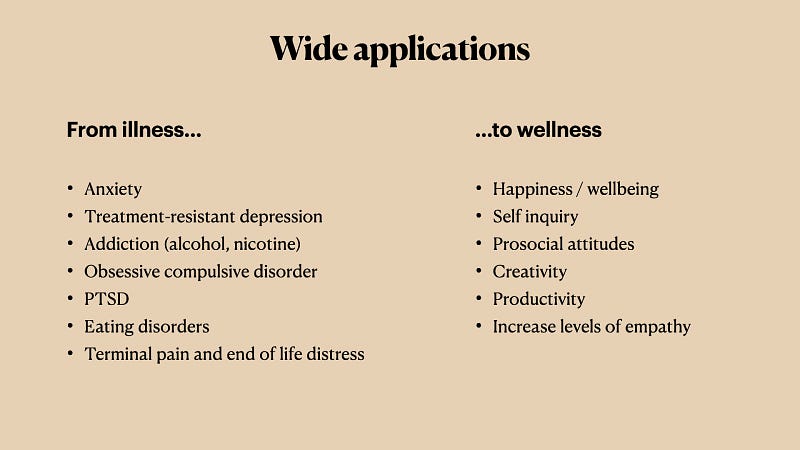

Psychedelics boast a broad spectrum of applications, ranging from wellness to illness:

While this extensive list may seem overly optimistic (akin to articles circulating on WhatsApp about miraculous cures like lemon juice and turmeric for serious ailments), the commonality among these conditions is noteworthy. Let’s consider a simplified view of neuroscience.

Neuroscience

The key seems to lie in an area known as the Default Mode Network (DMN), along with the brain's neuroplasticity. The DMN, which includes structures like the prefrontal cortex, plays a crucial role in higher-order functions such as self-reflection, emotional processing, memory, and future planning. This part of the brain, the most evolutionarily advanced, sets humans apart from other mammals and is often described as the conductor of our neural symphony.

These functions shape our identities and contribute to our sense of ego. A commonality among various mental health conditions is their tendency to create repetitive thought patterns and harmful narratives. A healthy brain exhibits flexibility; in contrast, depression, anxiety, and addiction can stem from a brain that has become too rigid in its connections. This rigidity leads to fixed pathways, making it difficult to forge new ones, a situation exacerbated by an overactive DMN.

Research led by Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College London in 2012 found that psychedelic experiences diminish DMN activity, allowing individuals to break free from excessive rumination and anxiety, fostering a more present and connected state. Since the DMN is closely linked to the ego, reducing its activity can lead to what is often referred to as "ego death."

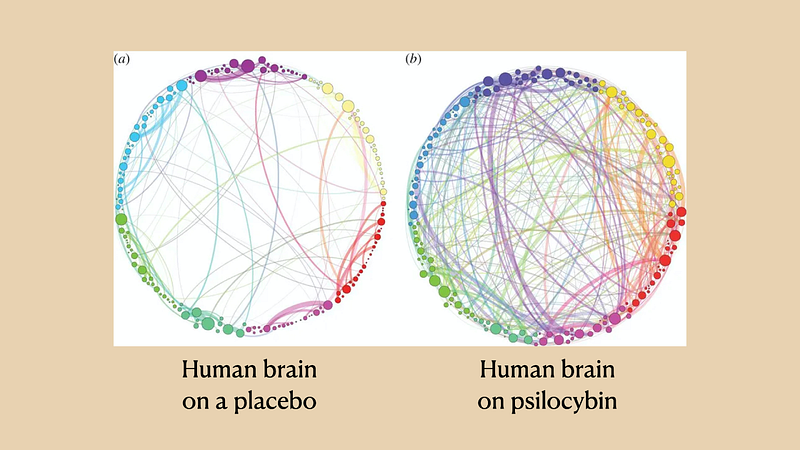

Further studies by the same research team in 2014 demonstrated that the brain under psilocybin operates very differently compared to under a placebo. Enhanced connectivity among various brain regions promotes more creative and insightful thinking, whether related to personal life or work.

The significance of neuroplasticity cannot be overstated. New neural pathways formed during psychedelic experiences may have lasting impacts, akin to the metaphor of sled tracks in the snow representing the brain's capacity for change.

Dr. Henry Fisher, Chief Scientific Officer at Clerkenwell Health, remarked that "the enhancement of neuroplasticity is crucial for the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics, enabling individuals to cultivate new coping strategies and unlearn detrimental thought patterns."

Research

According to Tim Schlidt and Daniel Goldberg from Palo Santo VC, there is a rich history of psychedelic research dating back to the 1960s, encompassing thousands of studies involving over 40,000 patients. Though many older studies lack rigorous methodologies (e.g., double-blind designs), they contribute to an expanding body of evidence supporting the efficacy of psychedelics. A double-blind study ensures that neither participants nor researchers are aware of the treatment assignments, minimizing bias.

The UK has a notable legacy in psychedelic research, established with the founding of the Beckley Foundation in 1998 by Amanda Fielding, which focuses on drug policy reform and scientific inquiry. This legacy was further advanced by research teams at King’s College London and UCL, paving the way for companies like Compass Pathways and Small Pharma.

Research momentum is accelerating, with the establishment of two dedicated centers for psychedelic studies in 2019: the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London and the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins University. Other institutions contributing to this field include UCL, Berkeley, and Yale.

Before delving into specific examples, it's essential to understand the drug development pipeline. Once a new molecule is identified for its therapeutic potential, it undergoes preclinical studies (lab and animal testing), followed by Phase 1 trials (initial testing on healthy volunteers), Phase 2 trials (testing on a small group of patients with the target condition), Phase 3 trials (large-scale, multi-center trials), and finally regulatory approval.

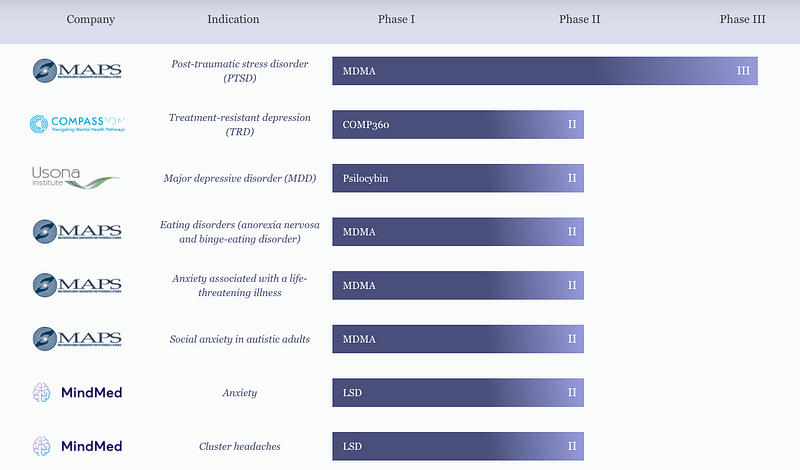

The website Psilocybin Alpha has created a valuable resource, the "Psychedelics Drug Development Tracker," which outlines key activities in drug discovery and development, listing compounds, organizations involved, and their progress stages.

Currently, 46 trials are listed in various stages (Phase 1, 2, or 3). Only one is in Phase 3, with an additional 22 in Phase 2, three in combined Phase 1/2, and 20 in Phase 1. There are also 24 preclinical trials noted. While this may not be exhaustive, another statistic from Clerkenwell Health suggests that over 60 companies are developing psychedelic compounds, with more than 100 clinical trials underway—an impressive figure.

The sole trial in Phase 3 involves MAPS, investigating MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This case study is significant; industry insiders note that MAPS' founder, Rick Doblin, strategically chose PTSD in veterans to attract bipartisan support in the U.S. This Phase 3 trial commenced in 2017, with expectations for completion by 2021, potentially leading to FDA approval as early as 2022.

MDMA and psilocybin dominate the most advanced trials, with some investigations into LSD, ketamine (which is already approved for therapeutic use), and ibogaine. The trials focus on severe health conditions to promote deregulation, including PTSD, treatment-resistant depression, eating disorders, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Granting legal access to effective treatments for these serious illnesses marks a significant paradigm shift. Once substantial progress is made, attention will likely shift toward exploring applications in areas like creativity, productivity, and emotional well-being.

The organizations driving these trials primarily consist of startup pharmaceutical companies, alongside a few non-profit entities. Major contributors include:

Non-profit: - MAPS - Usona Institute

For-profit: - Compass Pathways - MindMed - Cybin - Awakn - Small Pharma - Eleusis - Beckley Psytech

In summary, we've embarked on a comprehensive journey through the science of psychedelics, discussing their diverse applications, delving into pharmacology and neuroscience, and exploring the substantial research landscape in this domain.

Next, click here to read Part 4 of the series, which focuses on the safety of psychedelics.

Special thanks to Sean McLintock, Tom McDonald, Alastair Moore, Dr. Henry Fisher, Sjir Hoeijmakers, and Andre Marmot for their contributions and feedback on drafts of these articles.

[1] Aghajanian, G., Marek, G., Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/1395318#author-information [2] Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks, The Royal Society, December 2014 (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsif.2014.0873)