Zen and Spatial Cognition: A Journey Through Selfhood

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Space and Objects

This essay delves into the intricate relationship between space and the objects that occupy it. Historically, thinkers have viewed space as a fixed, absolute container where objects exist independently. However, with advancements in science, it has become clear that objects significantly influence the space around them, challenging the notion of their separation. This profound connection is exemplified in Einstein's Theory of General Relativity. A particularly intriguing aspect is the impact of spatial contexts on conscious beings. How does our orientation within space shape our self-perception? This concept is examined in the study by Proulx et al. (2016), titled "Where am I? Who am I?". To navigate through life's complexities, what perspective should one adopt toward the world? In this exploration, I will reflect on the teachings of Dogen, the founder of the Soto school of Zen, in relation to the previously discussed themes of spatial cognition.

Mass, Energy, and Space

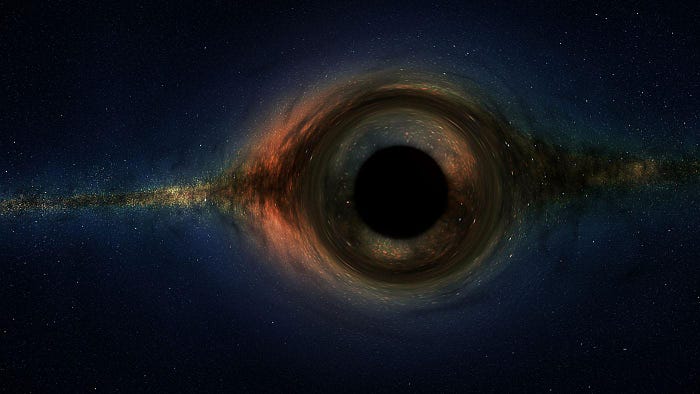

Our leading theories indicate that gravity is not merely a traditional force, but rather a result of the dynamic curvature of spacetime. The geometry of space is altered by mass-energy. The following illustration simplifies the concept of gravitation, depicting how a smaller sphere orbits a larger one due to the distortion created by the larger object's presence.

Einstein's Theory of General Relativity replaced the outdated view of a static spatial backdrop with a more dynamic understanding of spacetime, where objects and the space they occupy are intrinsically linked. The position of an object determines the intensity of the gravitational field at that location, which further influences the geometric layout of that field. We can observe the curvature of spacetime through a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. This occurs when photons from distant celestial bodies travel vast distances and are affected by the gravitational presence of significant mass-energy, leading to distorted optical images. These distortions provide critical insights into the quantities of matter that the photons encountered on their journey to Earth.

Form and Emptiness

The idea that objects influence space has been empirically validated, yet it has been recognized for a considerable time. This can be observed in the masterful interplay of black and white in traditional Zen art, where the white space is perceived not as a mere backdrop but as an essential component of the artwork.

Egocentric vs. Allocentric Perspectives

The distinction between these two spatial reference frames is clearly articulated in this statement:

Both reference frames are utilized in our daily experiences. As we navigate spaces, we alternate between these modes of perception, constructing cognitive maps based on how objects relate to one another and to ourselves. The advantages of meditation are highlighted in the following quote:

"Ultimately, such practices aim for non-egocentric, allocentric-like effects on personality, fostering a 'quiet ego' self-identity" (Wayment et al., 2015). An "allo-inclusive" identity, which incorporates the social and physical environment into one's self-perception, is advantageous as individuals with such identities report lower depression levels, greater satisfaction, and a stronger sense of connection to others (Leary et al., 2008).

Prioritizing certain modes of spatial perception appears beneficial for self-structure development. While scientific research quantifies well-being, the teachings of Zen master Dogen provide additional insights into this phenomenon.

Chapter 2: Dogen's Insights on Spatial Cognition

The first video features David Uttal discussing the importance of spatial cognition in STEM education, emphasizing the role of analogy in learning processes.

The second video features Robert Breedlove discussing the idea that space and time are not fundamental concepts, offering a thought-provoking exploration of reality and perception.

Dogen’s Genjo Koan

One of Dogen's renowned writings, titled Genjo Koan, is often interpreted as Actualizing the Fundamental Point. Kosho Uchiyama translates it as "the ordinary profundity of the present moment becoming the present moment." Both translations offer profound insights. A notable passage relevant to our discussion on spatial cognition is presented below through various translations by esteemed authors:

"To carry the self forward and illuminate myriad dharmas is delusion. That myriad dharmas come forth and illuminate the self is enlightenment." - Bokusan Nishiari

"That we move ourselves and understand all things is ignorance. That things advance and understand themselves — is enlightenment." — Shunryu Suzuki

"Conveying oneself toward all things to carry out practice-enlightenment is delusion. All things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self is realization." — Kosho Uchiyama

These translations beautifully articulate the dichotomy between rigid self-conception and the realization of interconnectedness. If we approach the world with a fixed notion of self, we remain in delusion. Conversely, allowing the world to inform our identity leads to enlightenment. When our identity is co-created through engagement with our environment, we experience a dynamic process of expression.

The references to spatiality are prevalent throughout these translations. Each quote emphasizes movement as integral to our interaction with the myriad dharmas (interpreted as the world or all things). Shunryu Suzuki's portrayal of things understanding themselves encapsulates this idea: there is no distinct agent; rather, understanding arises as life unfolds.

Cognitively, we cannot escape the use of both egocentric and allocentric reasoning. Our body naturally manages this, having evolved to do so. However, if we insist on maintaining a rigid self-concept, it may be prudent to dissolve the barriers between space and object. Emphasizing the interconnectedness of all things may be more beneficial than clinging to arbitrary distinctions. Instead of perceiving ourselves as agents moving through space, we might consider ourselves as movements of space itself.

Works Cited:

The significant study linking spatial and social cognition:

Three interpretations of Dogen's Genjo Koan:

Social and Spatial Cognition

Spatial metaphors permeate modern language. Abstract hierarchies, like power or competence, are often understood through spatial concepts (e.g., being in a higher position or level). We describe our relationships with friends in terms of proximity (Proulx et al., 2016). In teaching, we strive to bring learners closer to understanding complex ideas. The paper "Where am I? Who am I?" investigates the connection between spatial and social cognition, offering several valuable definitions of personality:

Through both genetic factors and the environments in which we are raised, we develop a specific perspective through which we interpret the world. This perspective dictates which information we deem relevant, thereby limiting our focus. Importantly, personality diverges from the concept of Self.

The Self is viewed as emergent, described as "a reference frame of the mind derived from the interaction between personality dispositions and the environment" (Lewin et al., 1936; Wayment et al., 2015). This reference frame can evolve in various ways, some being more conducive to well-being than others.