Bedbugs and Lice: A Historical and Evolutionary Perspective

Written on

The recent surge in bedbug infestations has caught the attention of global media, with reports indicating that Paris has become the epicenter of this troubling phenomenon. The New York Times cleverly dubbed the city "the city of light and bites," as locals refer to these pests as ‘punaises de lit.’

These unwelcome visitors have since spread to various locations, including hotels, public baths, and transportation systems in cities like Madrid.

Bedbugs are never solitary travelers. Insect-borne diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks are frequently reported, yet the historical context of other pests, such as fleas associated with plague, is often overlooked. Even today, outbreaks of diseases linked to these vectors still occur in regions like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, and Peru, according to the WHO.

All these infections share common insect vectors that play crucial roles in the narrative of infectious diseases. While differing significantly from an entomological standpoint, these vectors are unified by their bloodsucking nature—a trait that can be whimsically likened to both vampires and tax collectors.

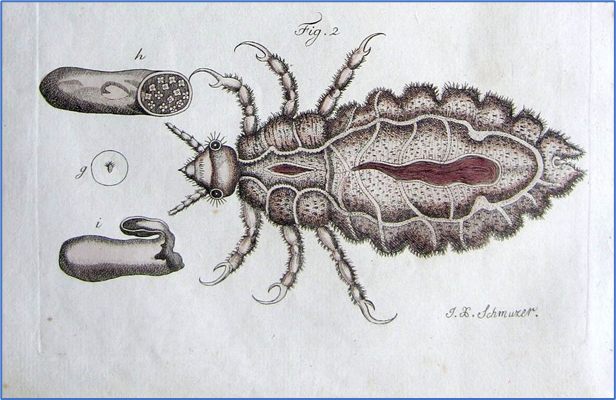

Lice, despite their lower profile compared to bedbugs, have long been familiar companions to humans. Various species of Pediculus infest but do not infect humans, animals, and birds. Specifically, we see head, body, and pubic lice, the latter colloquially known in Spanish as pipiolos.

The lifecycle of these parasites includes stages of egg (nits), multiple nymphal stages, and adulthood, with a maturation period that can span several weeks. This is crucial for understanding their epidemiology.

Nymphs and adults feed exclusively on blood and are obligate parasites, unable to survive outside their hosts. Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) feed on the blood of both children and adults, while body lice (P. h. humanus or corporis) and crab lice (Pthirus pubis) are more specialized.

Consider this: how many people have not had a childhood encounter with pipiolos in schools or daycares? The reality is that many have experienced the nuisance of lice at some point, often from head to toe.

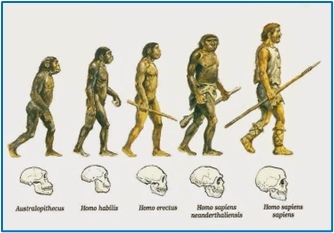

Humans and lice share a long evolutionary history, dating back approximately 25 million years. During this time, lice have adapted to live in the hair of our primate ancestors.

About 5.6 million years ago, humans and chimpanzees diverged on their evolutionary paths. Since then, human lice have become exclusive to Homo sapiens sapiens. Archaeological finds in Israel and Brazil indicate the presence of nits dating back 9,000 to 10,000 years.

The earliest lice likely transitioned from one primate species to another before adapting to humans. Throughout their evolutionary journey from Africa, anatomically modern humans and their lice have coexisted.

Interestingly, human lice have also been found on other human species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, illustrating a shared evolutionary path. This relationship makes lice valuable subjects for studies of human evolution, allowing scientists to trace historical adaptations.

Recent research by Marina S. Ascunce and colleagues has delved into the coevolution of humans and lice, employing nuclear microsatellite analysis to uncover fascinating insights. Their previous work in 2013 indicated geographical differences in louse populations, reflecting the impact of European colonization in the Americas post-1492.

This colonization period witnessed a significant influx of people, animals, plants, goods, and, inevitably, lice.

In a recent study from November 8, 2023, Ascunce and her team expanded their research to 274 lice across 25 locations, proposing seven evolutionary models through advanced computational analysis.

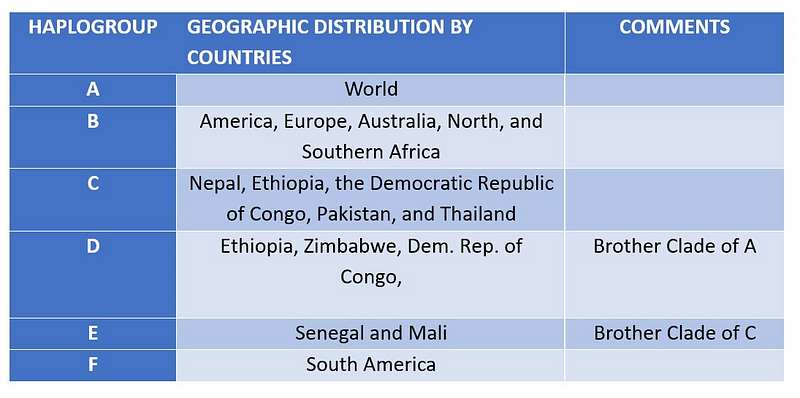

Traditionally, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has been the primary focus in lice studies, identifying three clades. However, recent advancements have revealed six distinct clades, each with unique geographic distributions. Notably, head lice belong to all mtDNA clades, while body lice are limited to clades A and D.

The study of nuclear microsatellites allows for a more nuanced understanding of lice inheritance, taking into account both parental contributions. This method is vital for generating genetic profiles and understanding population dynamics.

The analysis revealed that only 12% of the lice examined were hybrids, with a significant portion from the Americas, hinting at historical genetic mixing. The proposed models encapsulate interactions between modern humans and Neanderthals as well as patterns of global migrations, including the colonization of the Americas.

Additional analytical methods have identified two primary clusters of lice, with significant genetic differentiation between them.

The geographical structure of louse populations is notable, with analyses indicating high migration rates within nuclear clusters, contrasting with lower rates in mitochondrial haplogroups. Evidence suggests a genetic link between Asian and Central American louse populations, reflecting their shared ancestry.

To understand the limited hybridization observed, researchers hypothesize that genetic isolation between populations might play a role, potentially influenced by environmental factors and human behavior.

A longstanding myth is that Columbus and his crew introduced syphilis to Europe after their voyages. However, evidence points to an epidemic linked to events in Italy rather than Columbus’ journeys.

Two 16th-century manuscripts fueled the misconception of an Indian origin for the disease, yet this narrative has persisted for centuries despite its inaccuracies.

Returning to the topic of lice, one wonders if some will soon claim that Columbus inadvertently carried lice back to Europe, leading to another epidemiological crisis.

While we focus on head lice, we must not neglect the body louse, which is linked to historical diseases like epidemic typhus, transmitted by Rickettsia prowazekii.

Despite the rich historical tapestry surrounding these pests, the conversation cannot be fully explored here.

In conclusion, the story of lice and their complex relationship with humans is a testament to our intertwined histories. As we reflect on the past, it becomes evident that these tiny creatures have played significant roles in shaping human health and society.